|

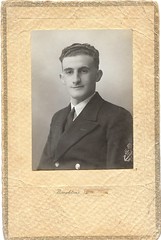

| Image by stuartaken via Flickr |

How does a writer enter the mind, heart and soul of a reader

and persuade a mature human being that the fiction purveyed is true enough to

deserve and elicit an emotional response? Of course, the question itself

suggests that every writer does this. But we all know there are writers who

succeed in the market place without ever stirring any deep emotion, relying on

the pace and action of their stories to maintain the interest of the reader.

Such writing invariably leaves the thoughtful reader unsettled and unsatisfied,

as if they've devoted time and energy to a pursuit that has failed to reward

them with a fully rounded experience. For me, such writers might persuade me to

read one of their novels but I'll never return to waste more time on such

superficial entertainment. It serves a purpose, of course, but holds little

appeal for me and many other readers.

If the writing of fiction is about anything, it's surely about

providing the reader with a multi-layered experience full of emotional content.

As a writer, I want to entertain, of course. But I also want to cause my

readers to laugh in amusement, cry with empathy, gasp in surprise, wail at

injustice, call out in fear, retch with disgust, pause in thought, tremble in

anticipation, wince at cruelty, warm with erotic response, scream in terror,

applaud at justice, weep at despair and

cheer over a deserved outcome.

But how are such responses to be achieved? People are so

different, so varied in outlook, experience and education, that it must surely

be impossible to get under their skin in this way? Well, perhaps it isn't

possible to succeed with every reader on every occasion. But it clearly is

possible to form the desired response in enough of your audience to justify the

time, energy and effort needed to invoke the emotion you're aiming for.

So, how does it work?

I suspect the most important factor is shared experience. All

of us go through the basic events of life; births, deaths, illness, falling in

love and out of it, fearing the unknown, having sex or getting none, admiring

some natural or man-made phenomenon, witnessing a natural catastrophe. We may

not experience all of these events personally, but we will have at least some

awareness of them through our family, friends, acquaintances and the

ever-present media. There is, therefore, some fellow-feeling which can be used

as a platform from which a writer can launch an assault on the reader's senses.

I'll give a couple of personal examples, since these are

things about which I know.

My real father died before I was born and I was raised, from

the age of four, by the man who later married my widowed mother and called

himself my father. I was loved, cared for, appreciated and nurtured. I've no

cause to feel in any way that I missed out on anything due to my real father's

untimely death.

But. Yes, the 'but' is the crucial aspect here.

But, I always felt that I was incomplete because I'd never

known my biological father. Because of this, I'm susceptible to certain

elements in fiction. One of these is the situation that drives the hugely

successful movie, Mama Mia. The

heroine, Sophie, wants to know who she is before she gets married, and sends

invitations to each of the three men she identifies as her possible father.

Now, this motion picture has much in it that should, by the measure of many,

not appeal to an average guy. It has been much lauded as a picture for women.

That it's also a musical, lends it even more of a feminine appeal in the minds

of many. But, because I absolutely understand, empathise with, Sophie's desire

to know about her father, I find the story moving. It touches me in a way that

probably evades many men. There's a link for me. And that's the point. I

respond to the emotional element that drives the story because I have direct

personal experience of the central emotion of longing to know.

Another incident that never fails to move me is the denouement

of The Railway Children. As Bobbie

waits on that railway platform and her father appears through the mist, I'm unable

to prevent tears falling. And it matters not that I've seen both recent

versions of the film on more occasions than I should. The power of the emotion

remains.

Why?

I can identify two entirely separate reasons for this one, I

think. The first is that I'm a father and have a strong love for my daughter. I

can empathise with the way both a father and a daughter must feel during a

period of prolonged forced separation. My personal experience lies in the

necessary absence of my girl as she attends university. But there's a second

factor at play here. I have a deep and enduring concern for justice. Injustice

wounds me and always has; perhaps I suffered some unjust event as a child and

this lurks beneath the surface of my consciousness to elevate the quality of

justice into something of paramount importance to me. I don't know; but it's as

good a reason as any for my concern. In The

Railway Children, of course, the father returns from a spell in prison

served for a crime he didn't commit. So, the daughter/father reunion is

enhanced as an emotional experience for me by the fact that justice is

restored. Hence, I think, my empathy and my inability to prevent the tears.

I use these two examples to demonstrate how powerful a tool emotion

can be for the writer.

Not only the most obvious emotion, that of love between

adults, as embraced by romantic fiction authors, but all emotion. The reader

needs to be exposed to the emotional spectrum as experienced by the characters,

to feel these emotions, not simply to be told that the character feels them.

'Rose felt the sorrow of

loss at the death of her baby.' This tells

the reader what happened. 'Rose gentled

the tiny crumpled cot blanket in trembling hands, hardly aware of the damp

trails she left as she brought it close to her face and inhaled the scent of

that small perfect person she would never hold again.' This shows the reader her emotions. And,

because the author will have built previous experiences into the writing,

making the reader empathise with the character of Rose, the reader will

experience the feelings of loss and utter devastation such an event gifts the

victim.

This is one example of how it can be done. So, the writer

engages the reader with the character(s), manipulates the reader into a

relationship that involves concern and fellow-feeling. Where the thriller

writer might get away with generic description and superficial emotional

content, relying on pace and action to drag the reader through the story, the

author of almost every other genre must actually become his characters, in the

same way a good actor does, he must feel what the characters feel, in order to

convey the real emotions experienced by the people who act out the tale. Only

then will the reader experience what the character feels and be moved, amused,

shocked, aroused or whatever is appropriate to the situation.

It takes a clever

combination of the right language with a description and presentation of character

that persuades the reader to care. If the reader really doesn't give a damn what

happens to the character(s), then the author has fallen at the first hurdle and

might as well take up some other activity. It's for this reason that most

serious (serious in the sense of intent rather than style) authors develop the

plot through their characters rather than forcing characters into a

pre-conceived plot.

If you're an author who wants readers to respond to your

writing rather than skip through the text on a mad dash to the end, you need to

be fully engaged with your characters and to allow them to dictate the

direction of the story. Only in that way will you find the necessary empathy to

share emotional events with them and, thereby, your readers. It's a demanding

process but one that brings great rewards when handled well.

The picture, by the way, shows my biological father, Ken Burden, about whom I've recently learned a good deal from his surviving sister, my 98 year old Aunt Vera.

6 comments:

Simple Stuart, at least for me. A writer gets my attention by his developing 'voice', something which takes years to mould, by constant, no endless hours of writing. Compared to the way I write today, my first published novel makes me shudder. So, would I judge a writer based on one work? No. I will never judge him. Instead I will sample each piece he writes. Far to many these days dismiss someone out of hand, merely because their first experience with the writer in question was not acceptable to their own way of thinking. J.R.R Tolkien was turned down for the Nobel literature prize, by its haughty committee who deemed that he was no story teller. Oh how wrong they were.:D

Thanks for this, Jack. There are only so many writers we, as readers, can find the time to follow in depth. With hundreds of thousands of books published every year, it's impossible to read more than a tiny proportion. So, for me, it's vital that an author engages me in the first piece I come across. Frankly, I don't want to read the pieces he's used to learn the craft: I don't think those should be foisted on the public. Of course, I recognise that I may miss out on something worthwhile from a rejected author who improves, but my limited reading times makes it inevitable that I'll miss out on so much anyway.

As for JRR Tokien; I read Lord of the Rings many times as a young man, but last time I read it I wasn't so impressed, and, of course, his work is full of myth that he borrowed from Norse and early British tradition, rather than original ideas. Oh, he tells a good tale, of course. But not what you could call an original writer. And The Hobbit is painfully condescending, isn't it? I know this is at variance with popular opinion, but it's what I think.

Many thanks for your views, Jack. I always welcome them here.

A thoughtful and thought-provoking blog, Stuart. I, too, always cry at the denouement of Railway Children, when Bobby's echoing voice shouts "Daddy, my Daddy". I think the problem these days is that life has to be instant gratification and so has no place for development. Hence the success of writers like Nora Roberts whose novels are all the same with name changes, of course. Damaged boy meets damaged girl, sparks fly, they hate each other, they cannot help being attracted. Denouement they have wild sex and commit. Yawn, yawn. Even when some of these writers have a series published featuring the same character, that character seldom grows and develops understanding and self-knowledge. And that is the big problem facing those of us who would love "success" but want to write "good" fiction. Answer to this - absolutely no idea.

Thanks, Avril. I'm wondering if the only solution is to write something superficial to get a following and then introduce those readers to the better fiction? I don't know, but it's an idea.

I've always believed that real emotions developed through real life is the best formula for depth. Characters we recognize, events we can visualize, common human threads: all of these lead to a great expression of humanity.

Having just finished a novel where the main character has the emotional depth of a peanut, and the ethics of a supernova, I can truly relate to what you are saying Stuart.

I hope readers of my novels and stories will find exactly what you describe here. I work hard to see that they do!

Wonderful post.

I suspect that peanut guy was in a thriller, Dave. There's no doubt that a life characterised by deep experience will help a writer give depth to his work. Good luck with your writing.

Post a Comment